Sunday book review – Endemic by James Harding-Morris – Mark Avery

Endemic species are those found (in the wild) only in a particular area so Britain’s endemic species are those found in Britain and nowhere else (in the wild at least). Such species are interesting as indicators of the workings of evolution since the last ice age and are ones whose futures lie entirely in our hands. This book is about the author’s interest in such species and his quest to find quite a few of them.

Such books, ‘naturalist in search of lots of species’, have become quite numerous and some are global in scope, some national, some conducted in a calendar year, some on birds, sometimes rare birds, many on plants and a few on other taxa such as bats.

Personally, I love these books and always find myself rooting for the author(s) as they have successes and failures in their quests. If they are well written, and include some interesting people as well as some interesting wildlife, then they are sure-fire winners with me. This book was a winner with me as it ticked all the boxes. But also because it’s a rather niche subject and an entirely novel approach. I wanted to know more about these species.

So, how long do you think the list of endemic British species is? Well, read the book! But this figure is quite elusive and changes all the time as species are split or lumped and scientific knowledge changes (I hope it’s improving). When I wrote Reflections I included a paragraph on endemic species (page 48) and found it difficult to find a reasonably authoritative figure. I may have estimated too low as Harding-Morris goes quite a lot higher but there are snags. Many of the species said to exist as British endemics have gone missing so it’s difficult to know by how much the list has been reduced by British, and therefore global, extinctions. Some of the purported species may have been misclassified and some may be species native to other countries which haven’t been recorded ‘at home’ but have been noticed here. If that sounds unlikely then consider just about the only beetle whose scientific name I remember, Aglyptinus agathidioides, which has been recorded only once in the world, and only in Potter’s Bar, and only in a Moorhen’s nest. And only in 1912, on the day The Titanic sank! The genus Aglyptinus is New World and so it is odd that one species was found over here. I once visited the Natural History Museum to see the type specimen of this species and it is a very beetleish beetle – but about the size of a full stop on a newspaper page. Wisely, the author didn’t go searching for it in the wild (though I gather others have) and doesn’t mention it. I think that’s very wise.

But apart from a dodgy and/or very elusive beetle, what are these species? At the easy end of the spectrum is the Red Grouse (see a bottle of Famous Grouse for a picture) which lives on the heather moorlands of the UK and is traditionally shot for recreation. We could all find one of those somewhere in the British uplands, although they are getting sparser and retreating north because of a variety of reasons such as climate change (almost certainly). During my life this species has switched between being regarded as a British endemic species to being an endemic subspecies of a circumpolar species and back again! But you won’t have to dissect its genitalia or use a hand-lens to identify this bird – its easy. The Scottish Crossbill is far less easy – calls are helpful and the size and shape of the bill (which is crossed at the tip) are helpful but not so helpful. Good luck with that one!

But that’s almost it for vertebrates and there aren’t huge numbers of invertebrates either – although a few more than I realised, some of which are simply fascinating.

Plants! That’s what most of them are. And quite a lot of them are different dandelion species, whitebeam species or bramble species. Don’t let that turn you off because, think about it, it’s really interesting. Why those species? And where are all these species to be found? You will find some of the answers and the answer to the question about how many of his target species the author saw in this book.

The trip to Lundy to search for the endemic Lundy Cabbage and the endemic Lundy Cabbage Flea-beetle and endemic Lundy Cabbage Weevil was a very good read. How did the plant evolve, and how did it ‘get’ two unique coleoptera? The chapter introduces us to interesting aspects of these three species but also the conservation issues of Lundy in general. I must revisit Lundy some time.

Endemic is well-written and has lots of information, lots of interesting species, lots of interesting people and some fascinating locations. Some are on tops of mountains, some are in caves, some are coastal and some are found in our cities. the author comes across as a nice bloke and he meets lots of interesting scientists, naturalists and conservationists as well as interesting species.

When I tell you of my Book of 2025, on Saturday 29 November in an extra newsletter, this book will be in the shortlist.

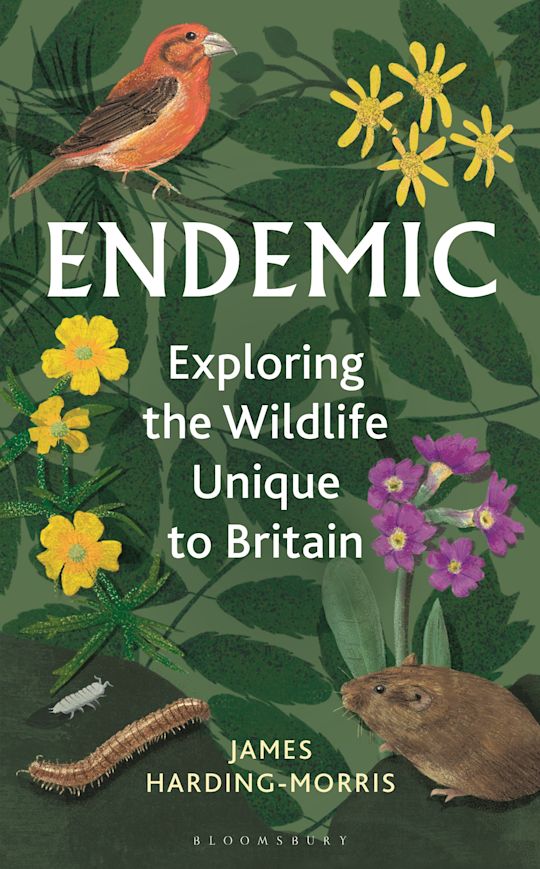

The cover? Adequate. I’d only give it 5/10.

Endemic: exploring the wildlife unique to Britain by James Harding-Morris is published by Bloomsbury.

[registration_form]