The Bhagavad Gita – Radiant Bliss

This series of four articles by master Dru Yoga Teacher Patricia Brown was first published in Australian Yoga Life. It is republished here with the author’s gracious permission.

The Bhagavad Gita, also known as the song celestial, is probably the best known and most loved of all of the great Indian philosophical works. It is part of a group of ancient Vedic writings known as the Upanishads in which a seer or luminary teaches a student by means of a discussion or discourse.

“When disappointment stares me in the face and all alone I see not one ray of hope, I go back to the Bhagavad Gita and immediately begin to smile in the midst of overwhelming tragedies.”

– Mahatma Gandhi

Five thousand years ago the great and noble warrior, Arjuna, prince of the Pandavas, stood on the battlefield of Kurukshetra and surveyed an opposing army.

Suddenly and unexpectedly, for the first time in his life, he felt fear. He began to tremble and sweat, his knees buckled and his hair stood on end. Why should he suddenly feel so much fear? Much like the ancient Greek hero Achilles, he had never lost a battle, and in the past, had proved himself invincible.

The only difference between this and any other battle was that this time he was being asked to fight against members of his own family. The Kauravas were people he had grown up with and whom he loved dearly. This is the setting for this wonderful epic.

Personal journey

When I initially read the Gita during my first yoga teacher training, it was such a struggle to finish it. I did succeed, but as you can imagine, I had no desire to revisit this scripture again. For me, it simply made no practical sense, as is often the case for others.

Fortunately, all this was to change during a Dru Yoga retreat in 1999. I came across a publication called Walking with the Bhagavad Gita written by Dr Mansukh Patel, Savitri MacCuish and John Jones. This book encompassed the first six chapters of the Gita but it was presented in a way that truly captured my interest.

The usual presentation of Gita slokas was maintained with verses written in Devanagari (the ancient Hindi script) and modern scripts, plus regular accompanying translations. The introduction of this particular publication had a description of each main character and its symbolic representation and also offered a colourful expanded story of the events relevant to each chapter.

The language was starting to make sense at last and I was drawn in by the beautiful, artistic drawings depicting the leading characters. However, it was the verses presented as a gripping story that really held my attention! After reading the story on that first night, I was very curious about what was yet to come in volumes two and three!

At last I felt I was beginning to understand what this ancient scripture was really about. The ‘song of the Gita’ had spoken to me. I could not let it go out of my life without trying to unravel its sacred message.

I wondered why the wisdom within this beautiful book was not more widely known, and then I discovered that many great people used the Gita as a source of wisdom and refuge during turbulent times.

Throughout the past five years I have incorporated this ancient scripture into part of my daily practice. The beauty and wisdom held within each page has begun to unfold for me. Interestingly, the Gita has become a living being! Master teachers of the Gita tell us that, “the answer to every human predicament is held within the pages of this text”. So why wouldn’t we, as spiritual beings on this human journey, want to throw ourselves into the ocean of these teachings?

Great people and the Gita

The Gita has been read by some of the world’s greatest thinkers. Albert Einstein said “When I read the Bhagavad Gita, everything else seems so superfluous.”

Eknath Easwaran, educator and author, wrote about his first meeting with Mahatma Gandhi (who was a great Gita devotee). He said, “I wanted to know the secret of his power”.

Gandhi’s secretary began to read from the Bhagavad Gita on the first evening of his visit to Gandhi’s ashram (Mahadev Desai). He said “He lives in wisdom that sees himself in all and all in him, whose love for the Lord of Love has consumed every selfish desire and sense craving tormenting the heart…” As Easwaran watched the small brown body of Gandhi growing motionless and absorbed in meditation on those verses, he said, “I was no longer hearing the Gita, I was seeing it, seeing the transformation it describes”.

Gandhi himself said, “When disappointment stares me in the face and all alone I see not one ray of hope, I go back to the Bhagavad Gita and immediately begin to smile in the midst of overwhelming tragedies.”

So what is so special about this book that has the power to sustain and transform?

What is the Gita?

The Bhagavad Gita consists of eighteen chapters written in Sanskrit by the sage Vyasa. This poem of 700 verses is in the form of a dialogue between Krishna and Arjuna.

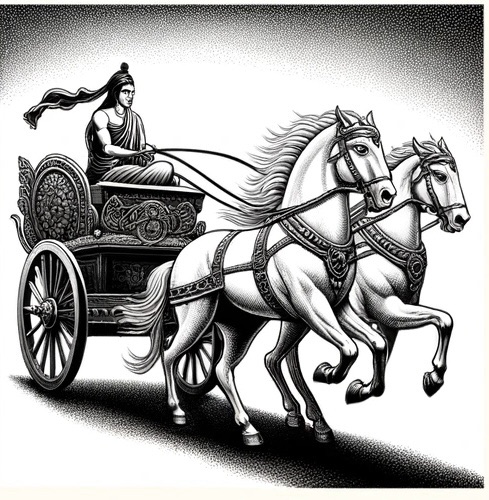

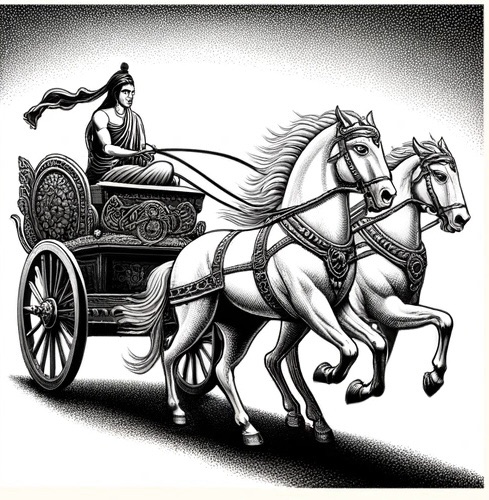

Krishna is the charioteer and Arjuna’s dearest friend, companion and teacher. He represents the higher Self. Arjuna is the archer representing the noble human being in conflict.

In this allegory, Krishna gradually leads Arjuna (you and me), out of a state of despondency in chapter 1 to a state of bliss in chapter 18.

This journey is ‘a giant leap for mankind’. It is made in small steps so that we, the readers, are able to accompany Arjuna as he gradually comes to understand what is really being offered to him. The sacred knowledge revealed by Krishna enables his student to rise to the very pinnacle of his human potential and to be victorious against impossible odds.

This hero, Arjuna, is me. He is also you. His challenges are mine and they are also yours. But his victory is ours. So how did Arjuna come to be in this predicament, standing in the middle of a battlefield between two opposing armies?

Background and characters

This great dialogue between Krishna and Arjuna takes place on a battlefield – the battlefield represents ‘us’. To more fully understand this, we should get to know a little of the background of the opposing armies who are the Pandavas and the Kauravas.

Both of these families are descended from Bhishma, a great warrior. Bhishma took over the role of fathering King Pandu’s five sons (the Pandavas) after the king died young. King Pandu’s brother Dhritarashtra (the father of the Kauravas) was unable to take the throne himself because he was born blind.

So Bhishma took responsibility for ruling the kingdom of Bharat until the eldest Pandava son, Yudhishthira, was old enough to assume the throne. Predictably, rivalry and jealousy arises between the families of these two brothers.

This happens despite being raised together and tutored by the very best instructors, especially Dronacharya, a master of military accomplishments of every kind. Dhritarashtra’s eldest son, Duryodhana, is determined to take the throne from the rightful heir, Yudhishira.

No scheme is too devilish for this ruthless, jealous young man. There was nothing the Pandavas could do that would appease his anger and jealousy. Just like the best of epics, the heroes have to combat attempted murder,arson, poison, a rigged gambling contest, broken promises, deceit and finally exile for fourteen years.

After their exile, Duryodhana refused to honour his promise to return their land. Yudhishthira, a peace-loving man, found himself faced with war as the only means to prevent Duryodhana from overpowering the entire kingdom. Arjuna, one of the five Pandava brothers, renowned for his courage and the favourite and most accomplished student of Dronacharya, is chosen to lead Yudhishthira’s forces.

In a chariot race as enthralling as that in the film Ben Hur, Arjuna and Duryodhana raced to Krishna to ask for his assistance. Krishna, said to be a representative of the Divine, gave them both a choice. One could have him as his charioteer with the proviso that he would not take part in the battle, and the other could have all of his armies.

Arjuna chose Krishna without hesitation. Duryodhana, thrilled to have Krishna’s great armies at his disposal, was convinced that he could not possibly lose the upcoming battle.

This, then, is the background to the famous battle on the field of Kurukshetra. However, it is also important to become more acquainted with the characters themselves and what they represent for us.

The Pandavas

In most stories the Pandavas would be called the ‘goodies’ but they actually represent the great qualities within us all.

Krishna represents the best aspects of ourselves and that part we long to identify with, the higher Self. He is a lifelong friend of the five Pandava brothers.

The eldest brother Yudhisthira (also known as Dharma Raj, the King of Dharma) is righteous, noble and completely unable to tell an untruth. He represents the very highest truth and dharma within us.

As mentioned before, Arjuna, that formidable warrior blessed with miraculous skills and indomitable courage, is very open, straightforward and willing to learn. He represents you and me.

The Gita is considered to be the ‘cream’ of the Upanishadd.

We face the same difficulties on the battlefield of life where we come up against all the different parts of ourselves that prevent us from realising our true nature.

Then there is Bhima, another great and powerful warrior, best known for his strength and sense of humour. He represents our deep indestructible power.

Of the remaining two brothers, Nakula is the skilled horseman, representing grace and divine beauty and Sahadeva is the wise and learned one who knows the past, present and future. He has incredible wisdom, although he will not reveal anything unless asked. He is indicative of our own knowledge and wisdom.

Draupadi is married to the five Pandavas (how this came about is another wonderful story in itself) and is known for her eternal, unending joy. She is the strength behind the Pandavas and represents our virtues. She shows us that part of ourselves that is irresistible to the highest source.

Gandiva, Arjuna’s bow, represents our self-will and egocentric defence. The chariot, driven by Krishna, stands for our physical body. The five horses are our senses that need to be skilfully guided and controlled by the Self, so that we are able to realise our true nature.

The Kauravas

It is tempting to call the Kauravas ‘the baddies’ but that label would be a disservice. They actually represent our negative aspects.

Dhritarashtra, born blind and unable to rule the kingdom, represents our blind mind which is ignorant of our true nature.

He is married to Gandhari, a loving wife who, in loyalty, blindfolded herself to support her husband. She gave birth to one hundred sons. She represents the intellect that chooses not to see. When the mind and intellect remain blind, they give birth to hundreds of blind desires that torment and destroy our life.

Their eldest son is the previously mentioned Duryodhana, a strong, powerful warrior who, together with his brothers, represents our lower egocentric nature.

Because they are born of ignorance, they contain hundreds of qualities opposed to dharma (life purpose), such as fear, anger, guilt, arrogance, doubt and pride.

Sanjaya, a Brahmin priest and faithful servant to Dhritarashtra and his court, is gifted with divine sight. He acts as the King’s eyes and stands for our intuition.

Dronacharya, skilled in archery and military accomplishments, is the beloved teacher of both the Pandavas and the Kauravas.

Bhishma is a most interesting character fighting with the Kauravas, as he is the noble and indestructible warrior/protector and grandfather to both the Pandava and the Kaurava families. His nature is beyond reproach, yet because of his allegiance to Dhritarashtra, he fights against the Pandavas. Bhishma and Dronacharya represent those positive qualities within us that we dearly love, but are ultimately a hindrance to the soul’s purpose.

Capture the scene of Kurukshetra

The beginning of the story sees Arjuna shouting to Krishna, his charioteer, to bring his chariot between the two armies so that he can clearly see who he has to fight!

The noisy, fierce, battle cry from the kettledrums, cow horns, tabors and trumpets was deafening in the stillness of the soft morning air.

The glorious sound of the warriors blowing their conch shells filled heaven and earth with a roar that tore at the hearts of those assembled. The plains were covered with tents, wagons, weapons, machines, chariots, horses and elephants.

On one side of the battlefield were the Kauravas, led by Duryodhana, while on the other side stood the Pandavas, led by Arjuna. Arjuna stood nobly in his magnificent golden chariot yoked by brilliant white horses flying the standard of the monkey god Hanuman, the Lord of the Wind.

From a distance, two men sat watching. Sanjaya, the great seer, with his gift of divine inner sight, witnessed all that was occurring on the battlefield which he recounted to Dhritarashtra, the blind king. The king knew in his heart that he had not tried very hard to prevent this war.

The stage is now finally set, the action is about to begin. This is the first of three articles on the Bhagavad Gita.

In part two wewill be dipping into the Gita’s treasury of insights to see how this ancient work can give so many practical hints on how to live with greater joy and freedom.

*In these articles the interpretation is drawn from the book “The Dru Bhagavad Gita”